MANA ATUA AND KNOWLEDGE SYSTEMS

Mātauranga Māori

Literal definition is Māori Knowledge

This is the knowledge that has been passed down through whakapapa korero originating from tipuna.

It encompasses all Te Ao Māori, the worldview, and its practices.

AUT. “Matauranga Maori”. AUT indigineous development and research, https://www.aut.ac.nz/study/study-options/maori-and-indigenous-development/research/research-expertise/matauranga-maori

Moorfield, James “Matauranga”. Te Aka Online Māori Dictionary, https://maoridictionary.co.nz/search?keywords=matauranga

It is important to note that te reo Māori is the anchor point for this knowledge, connecting people through to pre contact/colonisation.

There was an attempt of severing Māori from their mātauranga, principally through the banning of speaking te reo in schools, ensuring the younger generations could not connect. Though through will, and actions such as the Māori language petition in 1972 and 1985 Waitangi Tribunal Claim, there has been a resurgence allowing more people to openly connect with mātauranga māori.

NZ Government. “Maori Language Week”, NZ history, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/maori-language-week/history-of-the-maori-language

The oral tradition was broken down and redefined during this period of colonisation.

Rejected as real knowledge systems and placed in the realm of myth, distanced from the western scientific perspective. This concurred with placing mātauranga into a linear historical timeline – though the korero itself is anything but (as is the māori worldview), it is all time at once.

The stories do not fit into an ideology forged from a western perspective, and on that note, in collating/assimilating another cultures belief system will always be from one’s own perspective and worldview. Something will always be missing.

“Ownership redefined the tikanga of iwi and hapū relationships with the land, and sexism disrupted the complementary roles of Māori men and women. Racism reduced us to a warrior race or a compliant if noble savage, and arrogance turned sacred and complex understandings of the world into simple myths and legends”

Jackson, Moana. “Decolonisation and the stories in land”. E-tangata, https://e-tangata.co.nz/comment-and-analysis/moana-jackson-decolonisation-and-the-stories-in-the-land/

Tātai Aorangi

This is the astronomical knowledge used as a means of navigation as well as when to interact with the environment (planting, harvesting etc.), and even architecture.

This body of knowledge is embedded within kauwae-runga, the cosmological narrative, and feeds into the many traditional practices. One can whakapapa back to the stars.

Each hapu have their own stories that feed this tradition which gives tātai aorangi a richness and depth.

Henare, Hiona. “S.M.A.R.T” SMARTnz,https://www.maoriastronomy.co.nz/

This narrative can fit into the western perspectives of creation myths, it is interesting to note that most cultures across time have ended up with a creation myth that starts out of ‘nothing’ then an sudden appearance ‘explosion” happening.

“Tātai arorangi”. Project Mātauranga. Presented by Ocean Mercier (Ngāti Porou), season 2 episode 8, Pokapū Akoranga Pūtaiao: Science Learning Hub, 2012.

SMART – Society of Māori Astronomy Research and Traditions

A group that is revitalising tātai aorangi despite the loss of knowledge to cultural erasure

Placing the astronomical knowledge into a western scientific perspective, in turn giving it more prestige/acceptance.

Use of primary sources to find this knowledge – elders/tipuna

In some cases using written tradition to rediscover oral ones eg. Microfiche

Most resources from late 1800’s written record by Māori philosophers

There is a natural loss of knowledge across cultures due to our changed environment (urbanisation principally), children are less understanding naturally now than they would have been when exposed to the environment instead of hidden away from it. Though, merging indigenous and mainstream science centers to improve and unlock astronomy knowledge, ensuring survival through engaging tamariki and rangatahi about their knowledge. It is important to note that this knowledge has always been couched in a scientific/methodical approach, but the use of oral storytelling from a western perspective didn’t make it factual (see above writing from Moana Jackson).

Knowledge takeaways from video:

Use stars to denote season and time

Could tell by watching horizon in the morning

Lunar calendar important

28 to 32 days depending on tribe

Maramataka – lunar calendar

Bounty of crops would be called when matariki rose

Ratanui was thought as being a good time to plant as the full moon would draw water closer to surface – based on one tribe

This sort of knowledge was instrumental to surviving the environment

Everything reset with matariki to keep global time

Puanga and matariki both resets- depends on location where important

Puawhananga flower bloom- daughter of Puanga and Rehua

Why does a flower whakapapa to a star?

The relationships between the three are that the trees flowered in the months in between the appearance of the two stars, that were often denotations of winter and summer.

Rāwiri Taonui, ‘Te ngahere – forest lore – Flowering plants’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/photograph/14081/puawananga-flower2021)

Astronomy for voyaging

Used to tell direction through stars

Always rise and set in same spot so they can orient

Relative positioning – star compass

Waka at the middle of 32 points to tell sailing direction

Based all on memorisation. As a way of teaching – use stories to remember sequence of events by the stars

Knowledge is used to create – philosophies that underpin worldview will influence what you make

This is your Mahitoi, and is always important to keep in mind. Knowledge is embedded into the structure of our everyday, literally and figuratively. Tātai aorangi is used as a part of house design, and the star compass used in navigation is carved into the boards of the waka.

Kaitaki

In response to Rev. Marsden excerpt (taken from my 237131 writing) and revised with Barlows text.

Kaitiakitanga- guardianship – in most cases of the environment. With the understanding that the world of man and nature are one in concept. Though to move away from a humancentric view, kaitaki are often depicted/are as animals. They are the first signifiers that an environment is changing.

“if there is something amiss when members of the tribe go fishing, the porpoise appears to warn them of possible danger, and unless the warning is heeded, calamity is sure to strike.” (Barlow, pg 35)

Kaitiaki are the connection of the spiritual realm to the physical, left behind by tupuna to protect taonga. The stories told about kaiktiaki remind those to regard their own kaitiakitanga responsibilities in their everyday actions.

Marsden Text In relationship to the RMA act

Article 2 of the treaty – protect culture and way of life

Fundamental knowledge – oral tradition employs carefully constructed fables/stories/myths around which to assimilate a wealth of information and worldview. This differs from the western scientific viewpoint, we all have a basis from which we work off to create a worldview.

The other part of the excerpt brings us back to who should hold knowledge. Here it brings up an important fact of a lot of western knowledge tradition is noticeably short sighted and lacks a holistic view of the knowledge being shared. A classic example as described in the text is of the atom bomb, we created a way to destroy but no way to mend/clean up the results when we use it.

“Do you mean to tell me that the Pākeha scientists{sic} have managed to rend the fabric (kahu) of the universe? I said “yes”…… “But do they know how to sew (tuitui) it back together again?” “No!”.

“that’s the trouble with sharing such ‘tapu’ knowledge. Tūtūā will always abuse it.”(Marsden, pg 57)

I can think of a current example where the Kaitiakitanga of an area has come under threat is at Pūtiki Kaitiaki on Waiheke Island where consent was granted to extend upon a marina that would disrupt or destroy much of the areas traditional kaimoana sources, particularly mussels. This is on top of it being a harbour for little blue penguins. As a result there has been a concerted protection campaign to stop development proceeding to protect the kororā. Ana rea that has been looked after since pre colonisation is now under threat due to resource consent granted for the large boat owners to moor, further increasing the rate of inequality and gentrification of waiheke , while it will provide a slight increase in tourism from boat owners – it does not take into account the long term ecological effects to the islands inhabitants in order for business owners to get a few extra dollars in revenue.

Franks, Josephine. ”Rush to protect penguins at Waiheke’s Kennedy Point as developers move in“ Stuff News, updated April 12,2021, https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/124809764/rush-to-protect-penguins-at-waihekes-kennedy-point-as-developers-move-in

Marsden, Māori (Ngāi Takoto, Te Rarawa). “Kaitiakitanga: A definitive introduction to the holistic world view of the Māori” The woven universe: selected writings of Rev. Māori Marsden. Te Wananga o Aotearoa, 1992, 54-57.

Barlow, Cleve (Ngā Puhi). “Kaitiaki”. Tikanga whakaaro: Key concepts in Māori culture. Oxford University Press, 1992, 34-35.

Twitch, Tina Makareti

Parallels across cultures in creation myths

Big Bang/te koru/te po/te no marama

All shared threads and commonalities

All creation stories started everything at one point, then differ on what happened after that

“it is not that we believe stories, but understand what they tell us” (Makareti, pg 99)

In popular science twitch is often used as ‘twitch into life’.

Can be seen as a thread back to the inception of the universe or a framework by which we view connection.

Knowledge underpins creative practice

Philosophies manifest in art and design

Makereti, Tina (Ngāti Porou). “Twitch”. Shift, An Anthology of Winners of the Royal Society of New Zealand Manhire Prize for Creative Science Writing. Ed. Bill Manhire. Wellington Royal Society of New Zealand, 2012, 88-101.

Intro to Science, Iwan Rhys Morus

Western science is out own philosophy of understanding

What we believe to be true can be fluid, what is true can be proven false later

Unscientific is often used to describe ways in what science we choose to follow

Culture is important in what we decide to be true

Much like religion or magic is similar, though we consider that to be unscientific

How knowledge is circulated in different cultures

Cross cultural knowledge

‘uniquely human’ endeavour

Science is cultural and impacted by environments and social hierarchies.

Morus, Iwan Rhys (Wales), ed.”Introduction”. The Oxford illustrated history of science. Oxford University Press, 2017, 1-6.

MANA WHENUA

Huhana Smith Interview

The whenua that is being targeted by this project is the papa kāinga of Ngāti Tukorehe (Horowhenua) to rehabilitate the land from pastural farming practice since the beginning of the 20th century.

The space sits on a former occupied pā surrounded by a further cultural landscape that was heavily modified to allow for occupation by farmers. The rainforest and swamp that used to reside here was cleared and drained. This was a rich source of food and fresh water for the tangata whenua around the 1850’s when it was occupied, and is now only fit for grazing animals.

“everything has been engineered to push water out towards sea faster” (Smith, 2.46)

The only thing remaining in Māori land tenure was the burial site (the rest of the land went out of tenure in the 1880’s) up until 15 years ago when the farm was bought back by the iwi trust.

The land itself was sold by land speculators at the turn of the 20th century to the Kidd family (and subsequently was used as a capital entity in a western worldview). What was former papa kāinga is now administered as a tribal farm, and a place of research using matauranga māori to reestablish a connection to the land which leads to establishing a sustainable eco system (within the realm of climate research). (Smith,5.00)

‘the more you keep people away from the land, the faster you lose contact/relationships with the ecosystem’ [sic] (Smith,5.48)

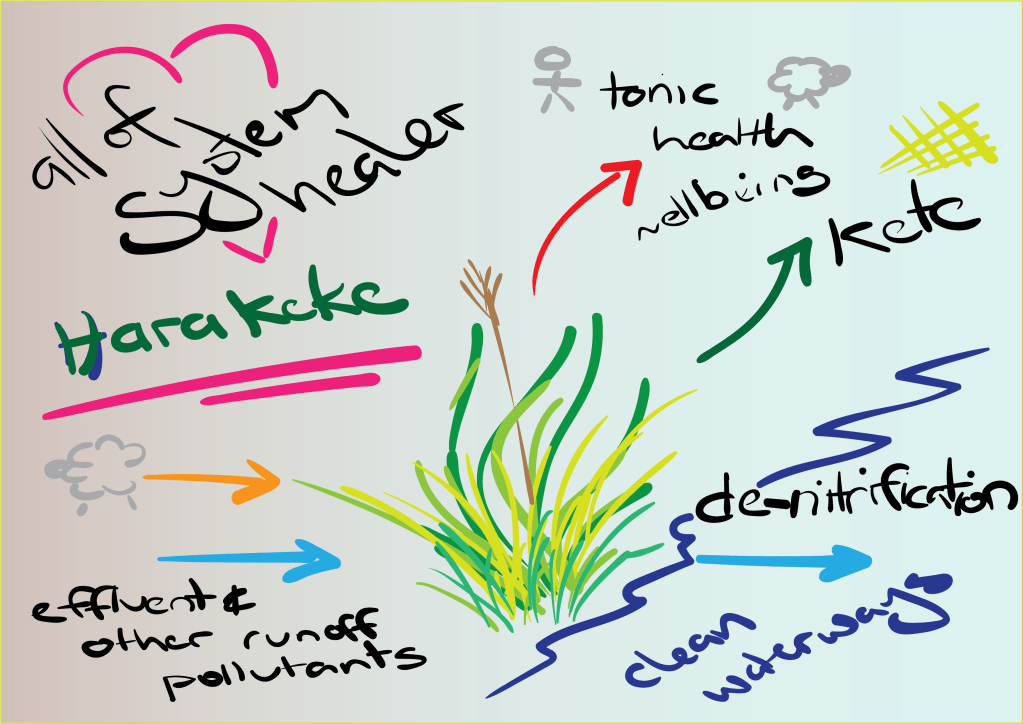

The aim of the project is to use harakeke (flax) to heal the waterway, as well as provide an alternative economic approach to the area instead of pastoralism.

This is an indigenous plant that is not only suited to the environment, but has been used for many generations and is part of the knowledge base for iwi.

It is considered to be an all of system healer. All parts of the plant can be used to retain the health of people and the environment, from the seed to leaf.

This is used alongside Western scientific views, where harakeke is understood to be great at denitrification of water. Especially effective when planted as a pā harakeke.

Denitrification can be as high as 90% if it is continually harvested and not allowed to mature.

This strongly combats the nitrogen and cattle effluent polluting the river. (Smith,8.00)

There is a focus on looking at creating a whole system out of the practice of conservation, creating by products from harvesting harakeke.

Allows pushing towards sustainable practice (fabric industry) while being culturally rich (whakapapa relationship) and engaging, economically viable, and socially responsible. (Smith,10.30)

‘What is purpose of a sustainable industry if people a few generations down the line do not also get to enjoy and be a part of the space’ – class quote

Harakeke as seen through whakapapa, a relationship that is about whole of system thinking. It is a non-linear world view that acknowledges ancestral information to inform future thinking.

Seen through korero around family, the heart of the flax is the children of the whanau and the adults the fronds on the outside. If you cut out the middle of the plant it will kill it, as well as the family.

A metaphorical connection, ‘we have severed those connections and need to get them back in the ground’ (Smith,14.30)

There is a place for art and design in this practice, as visual communicators can show what people need to be looking at. Getting people behind important projects and visions for the space, such as reintroducing papa kāinga. For artists, responding to the environment and industry in a way that speaks to the transformation of the space.

It is a place for universities to engage with matauranga māori, and help employ a vision for the mana whenua. (Smith,16.30)

There is a constant in being brought into and engaged with at a Marae Level, despite the diversity of talent coming through. Through Tikanga, it ensures that everything is protected and looked after – preserving the manaakitanga and kaupapa māori.

Moving through the Marae clears people to become part of the project, and create a relationship to the land.

This is a reciprocal relationship, and teaches people to interface and be comfortable in Māori environments. (Smith,20.00)

Gilbert, Greg (Canada). “Huhana Smith interview”. Youtube. Interview with Huhana Smith, 16 July 2018.

This project can be seen not just as regeneration of the environment, but of agency and knowledge for the people engaging in it. We are living entities within the environment, and not in charge of this relationship, we are co-dependant on these systems.

‘don’t save the bees, live in a way that it isn’t a problem’ – class quote

WHAKAPAPA

My understanding of whakapapa is about the holistic relationships within Te Ao Māori between not only individuals but in the environment too.

In human terms it can be considered as a genealogy which records the papa/layers along to the Atua, and origins of the universe. ‘we all come from stars’

“To understand the meaning of plant and animal whakapapa requires knowledge of not only plant and animal names but also their accompanying narratives. Typically, these take an allegorical form in which explanatory theories as well as moral principles are explicated” (Roberts et al., pg 1)

To explain whakapapa in the context of the quote, it would be useful to look at the example of the Tohoroa and Kauri. At first it would be amiss to see the connection between whales and kauri, one belonging to Tangaroa and the other to Tane. But as the korero goes, Tane when making Kauri decided to make the whale with legs – and it lived in the swamps. Then he decided to gift the whale to Tangaroa.

“The whale having a great time out in the ocean, decided to visit the kauri tree, and ask it too come enjoy the ocean with it. The kauri did not want too, so the whale gave the kauri its skin. When asked why, the whale responded, because one day you will be cut down for waka [sic]”. (Parata, 2.10)

This story provides pertinent information about ways to keep Kauri healthy. Whale blubber can be used as a fertiliser and an anti-fungal agent, which is very important at the moment for stopping the spread of kauri dieback. Now conservationists armed with this knowledge can extract the important enzymes used for the barrier cream to create another barrier agent.

Down south there is another whakapapa narrative, which speaks to how place and resource change how the interaction between systems change – narrative is not a monolith and serves to help spread knowledge important to that area.

This is the sort of knowledge that can be lost through the dismissal or lack of symbiosis between worldviews. There is a lack of consideration for the knowledge across many indigenous cultures, which will be explored shortly in the talk by Brain Pascoe. This knowledge is an important alternative to the Abrahamic worldview of ‘man will have dominion over all land’.

“Te tohorā me te kauri”. Haukāinga. Te Hiku Media, 1 September 2018.

Roberts, Mere (Ngāti Apakura, Ngāti Hikairo), et al. “Whakapapa as a Māori mental construct: Some implications for the debate over genetic modification of organisms”. The Contemporary Pacific 16.1, 2004, 1-28.

Other notes from Robert’s text is using whakapapa to talk about ethics in cross cultural context. The issue raised was around genetic modification. 82 Kumara were brought to NZ, and through government policy there are now only 3. This lack of biodiversity is dangerous to a crop especially if disease sets in.

How should we bio-engineer species in response to Tikanga?

This genealogical link has been severed, as an important ancestral connection should it be restored to maintain that whakapapa. It seems important to do so.

Ted Talk on Aboriginal Histories

The main takeaways for the class from this talk were:

The missionary projects and protestant work ethic is not talked about often but prescient when talking about the views of indigenous peoples as lazy. Especially when looking at environments that have less intensive land modification with the less communal privatised land modification of the environment seen in Europe, designed to extract maximum value often without view to sustainability.

It is a strong contrast to a pre-industrial way of living with the way land is used now.

Pascoe, Bruce (Yurin, Boonwurrang) .”A real history of Aboriginal Australians: The first agriculturalists”. Youtube. TEDxSydney, 24 July 2018.

MANA TANGATA

Michael Parekowhai, The Lighthouse, 2017, installation.

This is large scale installation, with a use of neon light. One can walk around the sides to view in, it is a built as house with only the façade. Inside sits a massive colonial figure made of metal with reflects all the lighting. The figure is supposed to give an imposing look, viewing you below them from a position of power, mad or repugnant. There is contradiction with the power balance and how it is slumped instead of the normal triumphant standing position.

The figure is a representation of Cook, the archetypical view of the coloniser in his captains uniform

Looks like a petulant child sitting on a table, which is a breach of tapu.

Even though sitting in the centre of the room, feels like it has been sent to the corner.

We are looking at the figure as it looks out at us, disconnected through the window separating the space. While we can walk around and view multiple perspectives, the figure will only have one.

Māori flag of united tribes colour scheme, speaks to mana, with red being the most important colour in the work.

A lighthouse looks out, but here we look in.

The work is installed at the end of queens wharf in Tamaki Makarau

The house itself is modelled on what we see as ow income state housing, which makes an immediate statement sitting on one of the most expensive bits of land in Auckland.

This housing was initially built for aspiring middle class pakeha that struggled to get into the housing market. Since then they have turned from a symbol of pakeha wealth into symbols of ghettoization and subsequently slum cleared when the areas and houses became desirable again.

Lisa Reihana, In pursuit of Venus [infected], n.d. Digital projection.

This work looks hand printed, in a large scale wallpaper format though with added moving figures. This is a piece that is in conversation with another work depicting the Tahitian welcome of cooks voyage.

We witness cross cultural knowledge sharing, seen in a peaceful and calming light evoked through the soft colour palette. There is a strong attention to detail around ornamentation, and adornment.

There are a lot of work done here to dispel the myths and exoticisation of the pacific in French wallpapering, such as les sauvages de la mer Pacifique from the 1800’s.

Details such as there being a flat open scene, with the Prescence of grass and non-native species, speaks to the sensibilities of what someone believed to be a beautiful tropical location, though looking more like a English rolling meadow. The Scenery is made as a perspective of the Europeans looking to exoticize the people, and as a result distance themselves. They only had the accounts of the voyagers of the time to work off, and even in that took liberties.

Lisa’s work seeks to settle this score and provide a more equal tempered decolonised view of cross cultural moments such as these, relieving the focus from figures such as Cook.

Text on the doctrine of discovery:

Tina Ngata’s text outlines the legalisation of colonisation by the catholic church beginning from the 15th Century. Providing a blanch carte for monarchies of Europe to subjugate peoples outside of it and the realm of Christendom. Papal bulls such as the Dum Diversas, Romanus Pontifex, and Inter Caetera set out this legal framework. It is important to note that during this period, states derived their power from god, so the Vatican was a seat of immense political power.

This set out a hierarchy by which one may exploit for finical gain over others, which is still seen in our financial system today.

“Importantly, these laws have never been rescinded since they were issued in the 15th century. They also sculpted a societal reasoning of European superiority over all who are non-white and non-Christian, accompanied by a sense of supreme European entitlement to all non-white, non-Christian lands and resources.” (Ngata, pg 3)

These structures of power set out by the Doctrine of Discovery have been cultivated and maintained, with many narrative fictions set up to describe the prevalence of white supremacy beyond the papal bulls. The idea that colonisation is a historical concept, or that it was invited, and has been beneficial to the colonised.

Tina Ngata was one of the people that set out to dismantle the doctrine of discovery, in a request to the UN. Though that has yet to be recognised. The Church is seemingly unwilling to rescind the papal; bulls as it would recognise their complicity in the suffering of millions around the world for centuries. It would also set precedent for land to be returned to indigenous peoples, as the legal framework by which that land was taken is no longer valid. It is easy to see why such steps in decolonisation have taken place, considering the wealth and privileged position that this still affords people.

TAPU AND NOA

Tapu – forbidden/restricted

Noa – ordinary/free from restriction

There is a fluidity to the terms, as with many Te Ao Māori concepts, and are evolved to suit the needs of the community.

“The spiritual state can change over time” (Ataria, pg 6)

An example of this is Rahui, a restriction based specifically around time. We often observe these at the moment by whole of society when life is taken. I remember a rahui on stepping foot on Ruapheu in 2018 after a death at the crater lake.

Tapu is in all things, there is always a practical and spiritual link, a holistic view based around a ‘common sense’ reason for things being tapu. It informs the importance of tapu in all aspects of our life.

A quick example from class was sitting on a table – it is not hygienic, as well as food being noa while humans being tapu. You do not want to consume someone else’s tapu, a great hara. Food has to be noa to be consumed.

An example of the interplay between tapu and Noa in things is the Kumara. Kumara comes from the Atua and is a part of a person’s whakapapa, and is therefore tapu. The process of cleaning and cooking kumara (which also makes it consumable for us from a physical perspective).

Tapu is not respected it is breached.

Breaches can be corrected in most cases depending on the hara.

Tapu and Noa can be challenged.

What are the reasons for having a less understanding in general society?

There is a much larger focus on tapu, which I have also inadvertently done here. Men are in charge of maintaining tapu and women noa. So naturally of course when ethnographers wrote about these concepts, they principally talked to men, and also probably were not allowed into women’s spaces or viewed them as less important. I also have a view that this also is feed by the nature of western thinking around legal rulings dominating how we act and behave in society, a strong focus on punishment and don’ts rather than do’s.

Whakanoa is the process of removing tapu and things being noa. This is often seen in Powhiri, sharing food, washing hands, and removing shoes to create a connection to the whare. Another example is washing hands after visiting burial sites or being around death.

In the Text this is talked about in the context of biowaste disposal. For much of European history sewage has been placed in water and flushed out to sea to remove it from settlements, creating a very important distinction between certain water systems. Though now we are finding problems of pollution infecting our noa water supplies, which is an important to keep a clean state for everyone.

Historically, biowaste was placed far away from waterways and papa kainga/pā. By doing so the waste would filter through the land before reaching the waterways to stop them being polluted.

We are now looking for alternatives to current systems, and looking to adapt and apply Te Ao Māori to wastewater treatment. If we know we can’t continue to rely on flushing away waste, we can take these lessons and learn to properly filtrate waste. It is important to think of this in terms of treaty partnership, which is supposed to be equaliser of cultures, and as partners we need to respect the manaakitanga of the land.

Ataria, James (Ngāti Kahungunu and Ngāti Tūwharetoa), et al. “From Tapu to Noa-Māori cultural views on human biowaste management.” Centre for Integrated Biowaste Research Report, 2016, 1-16.

TE REO MĀORI AND TE REO

PAKEHA

Tame Iti, on mana

Mana grounds you, roots you to the past/present/future

It comes from knowing who you are, your turangawaewae

It is a system of respect and understanding.

A way of seeing eye to eye – create a level from which to start from

Mana can be challenged, tested. You have to be prepared to stand up for it, as we are all deserving and equal to do.

“Te Reo comes from the world, it is the same as the tui or kiwi” (Iti, 4.57)

Here Tama iti notes an important grounding of Te Reo in its environment, it is of its place, and therefore important to the understanding and respect of the world. It carries the mana of the land and people on its tongue.

There is an example of the systemic erasure of te reo in colonial schools, and that to do so was to assert authority, and forgoe an understanding and respect. In essence trying to strip people of their mana. Which of course if you do not agree with this authority it is important to test the true edges of it, and fight back against it, they do not always have more mana.

This leads into the importance of protest in our society, it is a statement of standing ground and being visible to people that do not wish you to be so. In my turangawaewae as a trans individual, this is done every day, there is an importance in trying to be visible as possible despite those that wish us to not be. Our Mana will not be shaken. Tama Iti leads with important moments in recent history of resisting an authority that was unjustified, such as bastion point, women’s liberation, the springbok tour protests, tribunal claims.

“the mana of the people is equal to any authority” (iti, 12.20)

How does this affect us for art and design?

It is important to challenge the status quo , and acknowledge the concepts of Te Ao Maori like mana in our work. This is a way of engaging with people outside our worldview, and should gain a breadth of knowledge of other cultures/worldviews/practices.

This is important for me as a person who works in government. That the government is not the chief authority of the people, and should be held to task for actions with seek to disrepute and harm those it seeks to protect.

It is important to consider how our work is resourced, and whether our references are credible, we should be looking at primary sources, engaging with tupuna.

Consider the potential of appropriation of iconography and mana of others, what is appropriate to use.

Ask what is your work doing for the community/culture

Iti, Tame (Tūhoe). “Mana: The power of knowing who you are”. TEDxAuckland. Youtube, 17 July 2015.

Huhana Smith, on mana

“Mana in its broad sense is a subtle and pervasive influence of supernatural origin that exists throughout the universe.” (Smith, pg 94)

This quote is a lead in to speaking about mana as something that cannot be owned/claimed, it is given or bestowed by others. This in turn can express itself in authority and leadership. It is maintained through relationships to the people and the environment

Mana is an essential part of viewing the whole as something worth protecting, from the rights of children, to access health and education etc. It manifests this influence through many forms of expression and in particular for this text, mana reo.

Language is seen as an “intangible taonga”(Smith, pg 95). The entry point to any culture is through its language. It shows what is deemed of importance and value to a society, their worldview. It contains the matauranga of the people, and in this relationship to their mana. Post-treaty Aotearoa sought to erase this part of Te Ao Maori through adoption/forcing of te reo pakeha is the predominant language of the people. In doing so tried to remove the mana of the people, and the last 40 years a strong revitalisation effort has tried to redress this balance. The Māori language act was passed in 1987 making it an official language though not this alone will revive a language, but it is a recognition of the impact that language has in a connection of people to a culture, which is supposed to be of equal importance within our bicultural treaty state.

Smith worries that this narrative positioned about redressing mana should be challenged, according to Dr Rangi Mataamua there are “only 18000 fluent speakers … for language to remain viable, there needs to be a critical mass of speakers” (Smith, pg 100). There is also concern the quality of te reo being taught currently. All these issues should be cognoscente and addressed I order to nourish the taonga.

In my own life I principally hear te reo māori in school and government. In government, while the intention is there to make it a language of equal value to english, by involving tikanga into practice such as opening meetings with affirmations, it does still feel relatively tokenistic. Though there is a willingness I see from officials to work and become better in this aspect. At uni, I hear te reo principally only from those that are familiar with the language and te ao māori. There is a generalised fear of breaching or failing to uphold te reo to the standard that students feel it deserves, and without the requisite learning to support that te reo stays silent amongst the general population. My partner is currently undertaking te reo classes through the WCC, as a way of trying to reconnect with her own whakapapa and identity in the Hawkes Bay. Though she is still early on this journey and often struggles to remember her iwi, which speaks to the sense of loss of mana from the 20th century period where ‘miseginated’ families would prioritise their pakeha connections over māori ones.

Compulsory Schooling is vital if we wish to truly make an impact, it must start young and be integrated at all facets of society. While we are trending in the right direction, there is a lot of work to do.

Smith, Huhana (Ngāti Tukorehe, Ngāti Raukawa ki Tonga). “Mana: Empowerment and Leadership”. E tū ake: Māori standing strong”. Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2011, 92-143.

What have I learned about language?

It is Power,

Power to the people from which the land has sewn,

Of its place, in its place, unmovable,

Inextricably linked,

What seeks to take this from us?

Someone malevolent in nature,

It is not a mercy to deny someone their language,

I wish them the best in their grave miscalculation,

Kanohi ki te Kanohi

Te reo pakeha is important to me, as it is the language of my family. Yet as a person of Aotearoa NZ te reo māori is important to me, the language born of these islands connects me to this place I call home.

COLONISATION AND NATIONALISM

“In ‘established’ nations there is a continual ‘flagging’, or reminding, of nationhood. The ‘established’ nations are those states that have confidence in their own continuity, and that, particularly, are part of what is conventionally described as ‘the West’. The political leaders of such nations – whether France, the USA, the United Kingdom, or New Zealand – are not typically termed ‘nationalists’. However, as will be suggested, nationhood provides a continual background for political discourses, for cultural products, and even for the structuring of newspapers. In so many little ways the citizenry are daily reminded of their national place in the world of nations. However, this reminding is so familiar, so continual, that it is not consciously registered as reminding. The metonymic image of banal nationalism is not a flag which is being consciously waved with fervent passion; it is the flag hanging unnoticed on the public building”(Billig, pg 8)

A nation and state are not the same thing. While a nation is collective identity of a group, the state is the means by which authority is presided over a people, and most notably who holds a monopoly on violence. Most modern countries are considered a nation-state, a system of governing that levy’s a sense of ‘nationhood’ as Billig puts it, in order to exert the states influence. This can be seen as an extension of where a state derives its right to rule, such as how monarchies in Europe derived their right through god. It is also important to note that a nation can exist without a state, such as that of Te Ao Māori, a connection of peoples over a geographic space that have a similar identity through shared cultures and worldviews.

Umberto Eco’s work on semiotics is a gateway into understanding how a nation creates meaning through the communication of symbols/signifiers. The most obvious example of this would be a flag used to represent a people. It is through the medium of visual communication, creating a language of identifiers so one can tell their ideological stance. This can be seen in his writing ur fascism which understands the ideology of fascists as purely one of visual pomp, projection of power. The ultimate end goal of the fascist is to inextricably tie their perception of nationhood to the state enterprise, and by such create a monoculture in which those that lie outside are nothing and the greatest sacrifice is to the state itself. This is an extreme version of nationalism that is employed in many ways by the states of today, while in many cases not in your face, present and pervasive across the culture, the banal.

This leads to the question about what is a New Zealander? In a mainstream sense it easy to think of someone who is a ‘kiwi’, white bread, cricket, beach going, jandal wearing, nature loving, fish and chip eating person. The dominant view is of the anglo-saxon pakeha culture as being the main influence for how we visually construct a person that lives in this country. Never mind the large amount of diversity of cultures and peoples present, or the māori who were people of this land long before colonisation and globalisation. There is a hegemony rooted in white supremacy that dictates who and who isn’t called a kiwi.

Recently there was a terrorist attack at Lynn Mall in Tamaki Makarau which immediately turned into debates about refugee status and who should be let into this country. The fact being ommitted that this was only being discussed in terms of people of colour like the sri-lankan man who committed the act. The same thinking led to a shooting by a white supremacist at mosques in otautahi, the idea that a certain sect of people do not belong and not part of the nation they uphold. Where do they get these ideas, it is not out of thin air. The way we present ourselves as a nation solidifies these boundaries to close off. It is seen in the language used by media, constructions of this world around us so that we may not see out of it.

Media has been at the forefront of creating our sense of national identity. Converting the islands from a colonial state into our own proud self, free to express what ‘we’ hold dear. These days we can see this sort of national collective thinking about the nuclear free protests, whether or not everyone was on board this has been turned into a moment of national defiance, creating an underdog story, placing us on the world stage

‘punching above our weight‘

And now, to bring everything back around it is an advertisement campaign for steinlager to sell the national pastime – drinking beer. There is no doubt that semiotics are often constructed as way of selling you something, sometimes that is more of an ideology than a product, and those lines are becoming increasingly blurred. Creating an imagined communities and then selling them back to us.

The main connection between language, NZ nationalism and mana is the way in which place defines us. The language is built from the environment, constructed in a way that complements the world we inhabit. The language is then used in this way to ground us and tie us to the land so that we may have self-respect/pride/mana from living here. This is appropriated by the NZ state to create a national identity and reinforce its own mana to give authority to rule.

T. Smirnova, and I. Unzhakova. “Semiotic Knowledge about Mass Communication Umberto Eco and Problems of Comprehension of Digital Reality.” Цифровая Социология, vol. 2, no. 1, May 2019, pp. 17–23.

Eco, Umberto (Italian). “Ur-Fascism”. The New York Review of Books, 1995

Alpers, Philip (Pākehā). “You’re Soaking in it”. 1994. Brian Bruce Productions.

Billig, Michael (British). “Introduction”. Banal Nationalism. Sage Publications, 1995, 1-12.

Frain, Slyvia and H Hague, Rebecca.”This Steinlager ad distorts the truth about anti-nuclear protest in the Pacific”. The Spinoff, December 16 2020. https://thespinoff.co.nz/media/16-12-2020/this-steinlager-ad-distorts-the-truth-about-anti-nuclear-protest-in-the-pacific/.

Herman, Edward S., and Noam Chomsky.

Manufacturing Consent : The Political Economy of the Mass Media. [New ed.] / with a new introduction by the authors, Pantheon Books, 2002.

Kenealy, Robyn (Pākehā). “A “kiwi” at my table”. Unpublished (student essay), n.d.

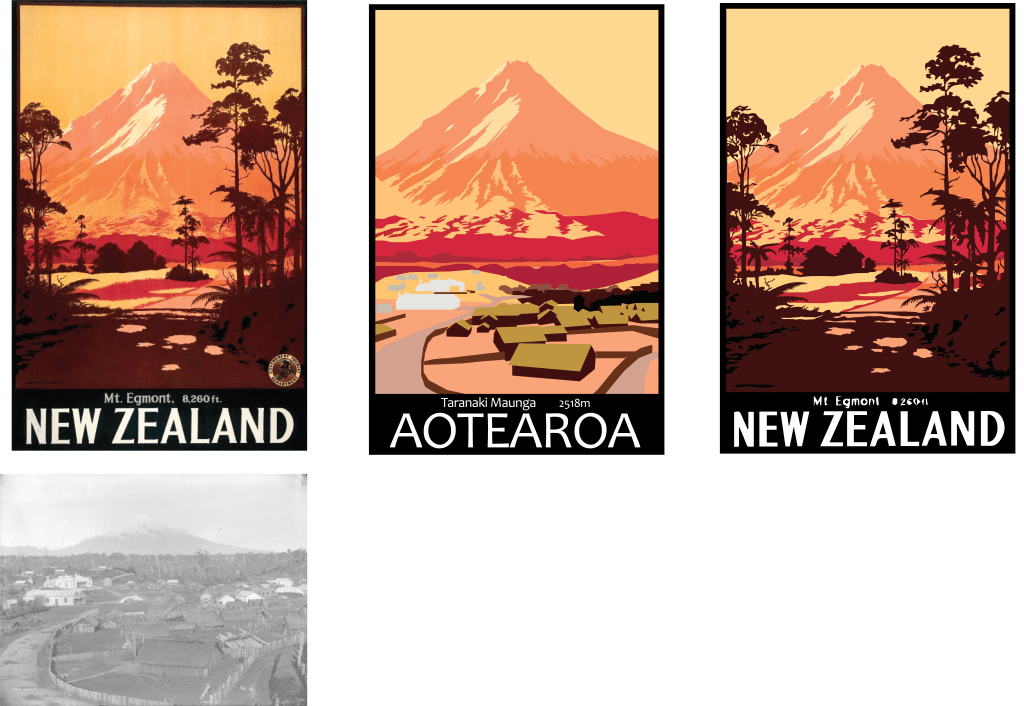

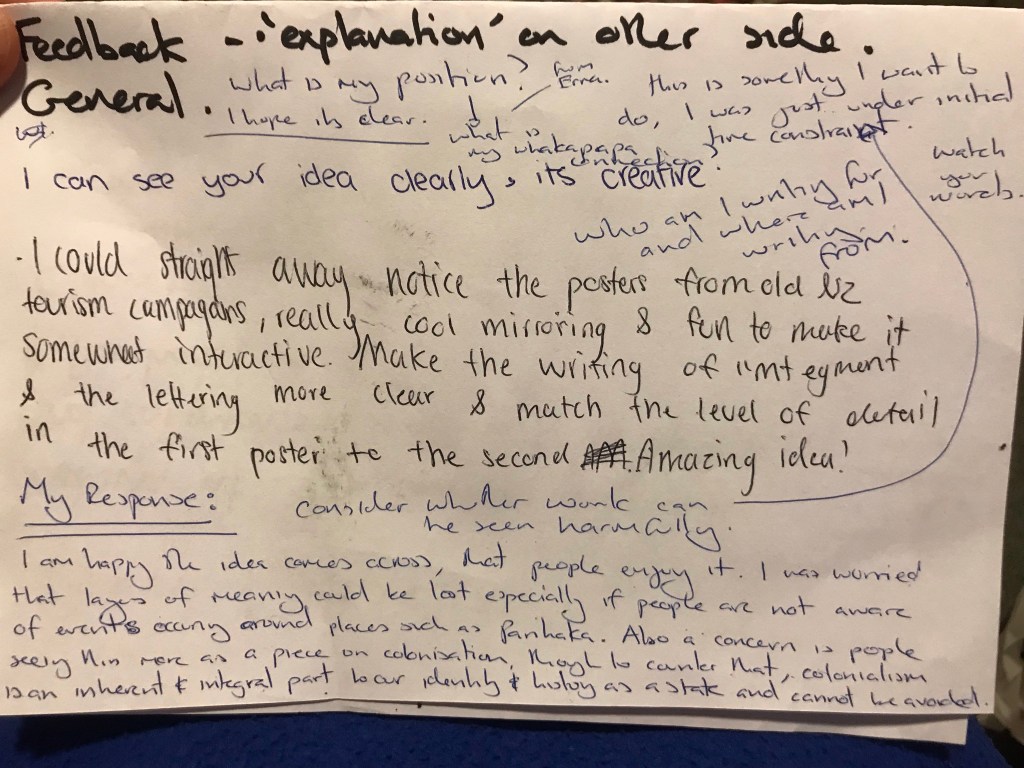

Assesment preperation and reflection

I wanted to create a physical work that responded to my feelings around my study into the tourism industries paving over social inequity to provide this clean/green image of the country. I zeroed in on a Gold levy print from the 30’s of Taranaki. The road in the print reminded me of how roads were built throughout the region to facilitate invasion and confiscation of land. I found an old photo of Parihaka from the 1880’s (around the time of the invasion that took place) and decided to use that as a symbol for this reflection on colonization and subsequent national identity.

Mitchell, Leonard Cornwall, 1901-1971. Mitchell, Leonard Cornwall, 1901-1971 :Mt Egmont, 8,260 ft. New Zealand / Government Tourist Department. G H Loney, Government Printer, Wellington. [1934-1937].. Ref: Eph-E-TOURISM-1930s-07. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22403038

Looking over Parihaka Pa towards Mount Taranaki. Collis, William Andrews, 1853-1920 :Negatives of Taranaki. Ref: 1/1-012106-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22763830

Reflection on my work now it is done. I felt that I could not fully give the adequate attention this topic deserves within the time frame/word count. I have a lot more I can explore and say, and I feel the nuance of any argument/debate is lost and my anger at injustice seethes through. I think this hits so close to home as I stated in my personal experiences of banal nationalism as a kiwi expat in my pre teen years. I was sheltered from the real impacts that this thinking has on marginalized people within our society, and the hegemony seeks to sweep these issues and visibility of people in hardship under the rug. I would like to continue this work to create both an external and personal response to these issues.